What difference does it make how we understand concepts such as transcendence and being?

Paul Ricoeur says we face a choice between bringing God down to our level or knowing nothing about God. “[T]o impute a discourse common to God and to his creatures would be to destroy divine transcendence, on the other hand, assuming total incommunicability of meanings from one level to the other would condemn one to utter agnosticism.”

I claim that we have to use the only mental tools available to us and so are constrained to think of God via human cognition. The real question is not whether we will bring God “down” to our level but which human concepts we believe are appropriate to apply to God and which ones think should be rejected.

Our understanding of Transcendence

Spatial concepts have a privileged place in human cognition as source domains so it is not surprising that these are used. Note that Ricoeur uses what is called the verticality schema (up/down) when he says we bring God “down” to our understanding. Western understandings of divine transcendence tend to think of God as beyond, above, higher, and far. These use the mental frame of objects in space.

However, this is not the only way to understand transcendence. If we use a different metaphor, for instance, then the meaning of transcendence can change. Moltmann, for instance, says “God is not ‘beyond us’ or ‘in us,’ but ahead of us.” Hence, God transcends us by leading us on the journey towards a destination. Biblical writers speak of divine transcendence in ethical rather than ontological terms when they speak about God as exemplar we should imitate such as when Isaiah says that God’s ways are not our ways because God forgives those who sin against God (55). Western Christians are so accustomed to thinking of transcendence in particular kinds of spatial categories that they typically miss other ways of understanding transcendence that involve interpersonal relationships.

Our understanding of Being

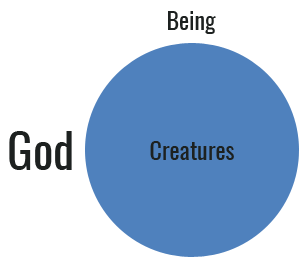

Being is thought of as the container of all that exists. Human are familiar with containers and the logical structure of the concept allows for three possibilities: (1) an entity is the container, (2) an entity is outside the container, or (3) an entity is inside the container, or (3). Applied to God this means God is either the container itself or God is outside the container or God is inside the container.

#1 God is being itself (God is the container). Think of a circle and label it God/being. All reality is God.

#2 God is beyond being (God is outside the container). Think of a circle and label it being. Put creatures inside the circle and place God somewhere outside the circle. Creatures have being but God is completely different.

#3 God is a being (God is inside the container). Think of a circle and label it being. Put God and creatures inside of it.

If God is an agent who interacts with creatures then God is understood as an entity within the container of being (#3). But placing God inside the container seems unfitting for two reasons. First, God is placed within the same circle as creatures, which makes it look like God is on the same level as creatures—we understand God like we understand creatures. This seems to “reduce” the greatness of God or bring God “down” to our level. Second, being is the container into which God is placed and since containers are larger than the contents inside them, then Being is larger than God and limits God. That is why some have concluded that God must be either beyond being or being itself.

Traditional theistic belief, generally affirmed by analytic philosophers of religion, understands God to be an agent who lives and interacts with creatures and so are comfortable saying that God has being. This means that God is a being who shares the characteristic of being with other beings. However, thinkers such as Paul Tillich and many in the Continental philosophical tradition fear that thinking of God as “a being” reduces God to an ordinary object in the world like a cat or plant which forfeits the divine mystery and transcendence

My main point: it is legitimate to think of God using the category being but if you do then you are constrained by the logic of the schema to three alternatives. Since the alternative of placing God inside the container seems inappropriate we are then left with God as being itself or beyond being. These options lead to particular problems of how we can know and talk about God and make it difficult, if not impossible, for traditional theists and Christians to worship God. The distinction (Gregory of Nyssa, Aquinas, et. al.) that we cannot know the being/essence of God but can know only the energies or works of God has its problems as well (e.g., we are not really talking about God when we say “God loves us”). The motivation for this distinction, to protect the divine nature from being reduced to the level of a creature, is appreciated. However, if we don’t assume the Neoplatonic idea that words name the essence of things and begin with the cognitive linguistic notion that human knowing is always an interactional and relational knowing, then we are free to think about the topic differently.

We don’t have to begin with the language of being. The language and categories we use have their own logics and we are not confined to the abstract notion of being. The biblical stories and much of the Christian theological tradition begins with the category of interpersonal relationships rather than the category of being. This is the move Jean Luc Marian makes when he says, “Does Being define the first and the highest of the divine names? When God offers himself to be contemplated and gives himself to be prayed to. . . . When he appears as and in Jesus Christ, who dies and rises from the dead, is he concerned primarily with Being? He goes on to say, “No doubt God can and must in the end also be” (i. e., God has being) but this is not the beginning of Christian thought. Marion claims that Christian reflection starts from the notion “God is love” rather than from the highly abstract notion of being.

This is the same sort of move Moltmann makes about divine transcendence. Why begin with the logic of non-personal entities such as containers instead of the richer category of interpersonal relations? The biblical writers prefer the interpersonal metaphors for God as did people such as Julian of Norwich. Cognitive linguistics explains why we have this preference: the category of interpersonal relations and the metaphors used to explicate it are far richer in their entailments regarding what we are to do. They give direction to our lives whereas the category of being does not tell us how to live. A God beyond being (e.g., Plotinus) or God as being itself (Tillich) tells us little, if anything, about how we are supposed to live in relation to God and others.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!